Women were always accompanied by other women from their family, neighbors or friends during childbirth. Over time, some began to be asked for help more often than others. In the 18th century, medicine developed significantly. This led to more attention on the need for better medical education. Schools for midwives were established and rules about this profession were introduced. This resulted in the creation of more documents containing information about their marital status, age and place of residence.

Midwife

From metrical records, especially older ones, we can usually learn something about a man’s social status. This is particularly true for records from the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century. This applies whether he is the father of a child, a fiance, or a wedding witness. It also applies if he is deceased or someone from the family. A woman, if she was not of nobility, was perceived by the social status of her husband or father. Among the professions available to a woman from the countryside, a common choice was being a servant to the nobility. Alternatively, they serve wealthier peasants. Hence, finding a record other than birth/marriage/death for a peasant or bourgeois woman at that time is very rare.

With one exception. A woman who helps with childbirth.

akuszerka, położna, Hebamme, повивалъна бабка

For centuries, these were women whose skills resulted from observation, experience and oral knowledge of older women. It is worth remembering that medicine began to develop seriously only in the 15th and 16th centuries. Obstetrics began developing even later. But, learning was reserved for men. Women, apart from noblewomen and nuns, not read.

Eventually that started to change.

17th century – the first schools in Europe.

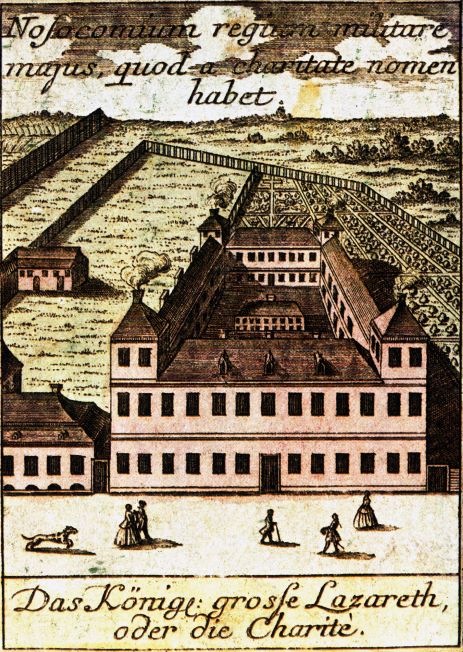

The first midwifery school for women was established in the mid-17th century in the Hotel-Dieu hospital in Paris. Over the next several dozen years, France developed teaching methods and an examination system that other countries began to follow. Approx. 100 years later, such a school was established in Germany in Strasbourg, followed by the Berlin Charité and several others.

The ideas of teaching the art of midwifery also reached Poland.

Midwifery schools established in Poland’s lands

The more educated people saw the urgent need to follow in the footsteps of Enlightened Europe. Poland in the first half of the 18th century was very depopulated after the wars. Epidemics of the earlier century contributed to this depopulation. The health of the lower classes was very poor. Sanitary conditions in both cities and villages were downright tragic. The need for help for women giving birth was indicated by Polish doctors educated at European universities. The problem was money (or rather the lack of it) and the gentry’s reluctance to “new things”. It is not surprising that these institutions began when reforms in Poland were attempted. This was under the pressure of the First Partition. The first school was established at the university in Lviv in 1773. This happened on the orders of the Empress of Austria, Maria Theresa. Over the next few years, Polish public midwifery schools were established in Kraków, Vilnius, and Grodno. Private ones opened in Siemiatycze and Mochylów. After the Third Partition, most of them continued to operate within the partitioning powers – Russia and Austria.

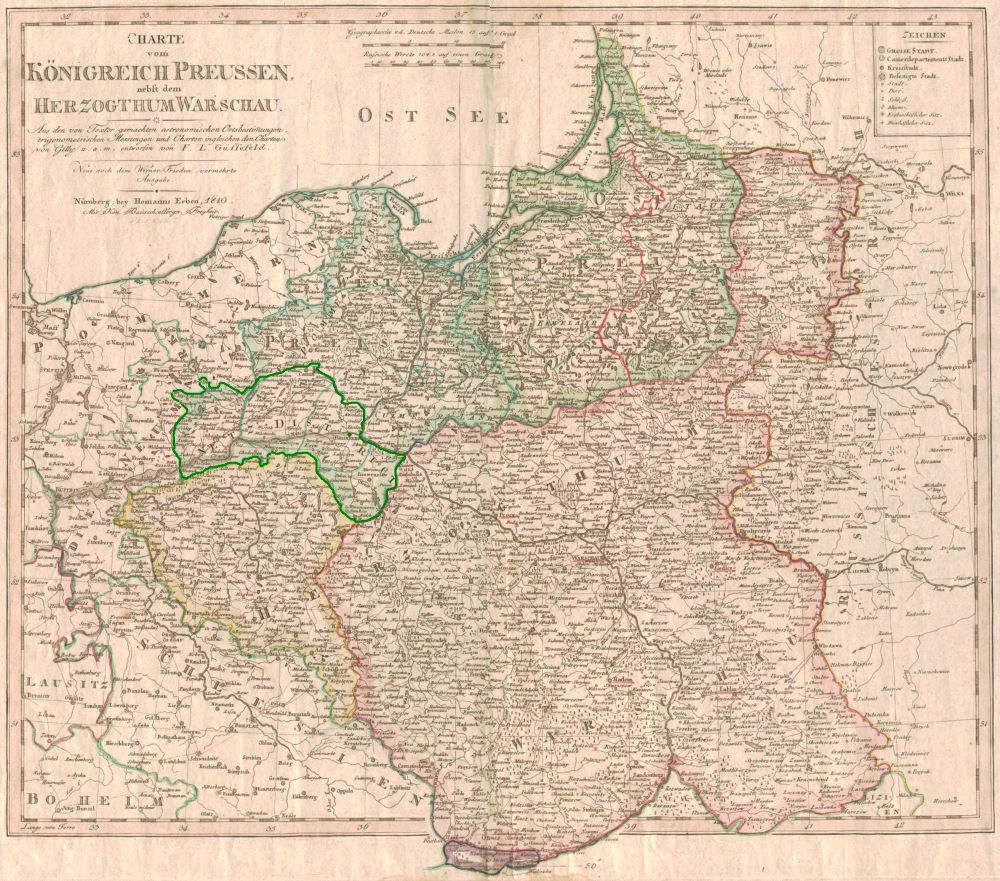

Prussia’s actions

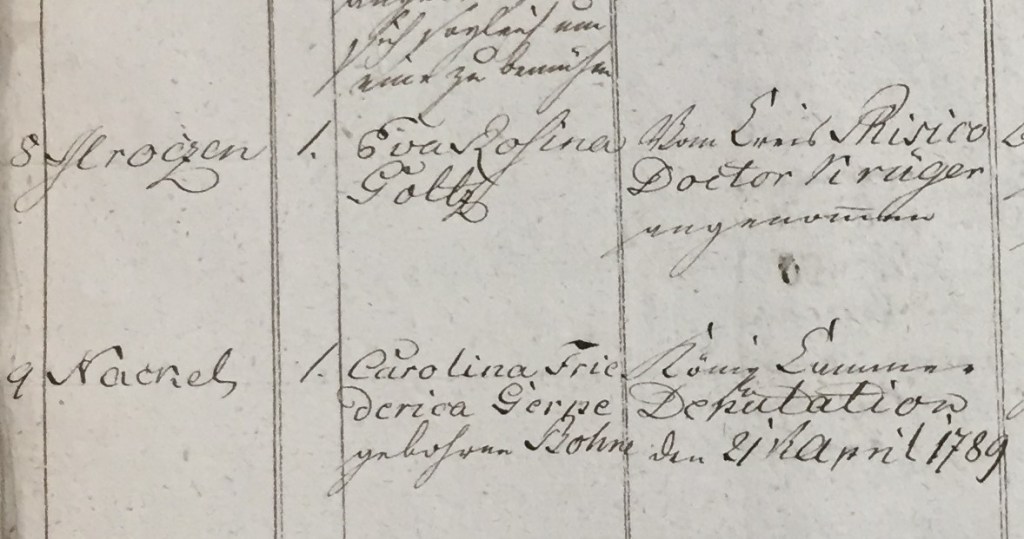

But the most steps to offer professional obstetric help in the occupied territories took the Prussian Empire. In the newly established provinces of West, New East and South Prussia, there was a new obligation. Individuals had to pass an examination before a medical board. Alternatively, they needed to have a certificate of completion of a midwifery course. As the closest one was in Berlin, five schools for midwives were established in the years 1799-1806. They were located in Poznań, Białystok, Gdańsk, Warsaw and Kalisz. They educated several to a dozen women a year. After the Congress of Vienna, only schools in Poznań and Gdańsk remained in the Prussian partition.

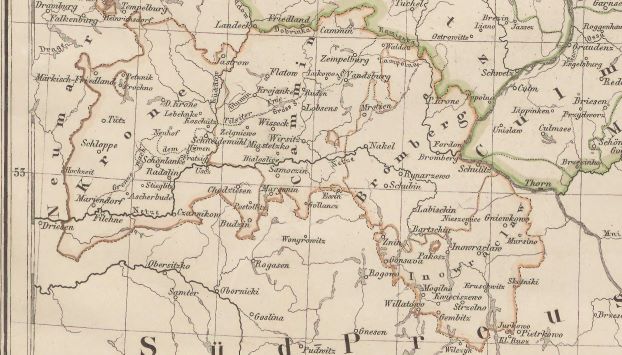

The Prussian authorities wanted to understand the needs in this area. They ordered a census of the places. It included information on whether there is a woman who delivers babies and what preparations she has. Such lists have been preserved in the State Archives in Bydgoszcz. It was here that the War and Domain Camera for the Netze District was based. This district covered the areas around four cities: Bydgoszcz, Inowrocław, Kamień Krajeński and Wałcz, i.e. part of northern Greater Poland and Kujawy area.

Netze District

This district was a separate structure, although connected with West Prussia. After the Congress of Vienna, these lands were incorporated into the province of Posen. It remained as a sub-province with its capital in Bydgoszcz. That is why there are so many mistakes when assigning towns from this area to West Preussen.

The census from Netze District is one of several similar ones created in the Polish lands incorporated into Prussia. One can also find there applications and approvals from individual midwives.

Files from the lands of South and New Eastern Prussia were subsequently incorporated into the Kingdom of Poland. They are available at Central Archives of Historical Records in Warsaw, mostly online.

Where areas still belong to Prussia, the files are kept in the state archive appropriate for a given area. So such documents are kept in the State Archives in Bydgoszcz.

Records of the Deputation of the War Camera and Domains in State Archives in Bydgoszcz

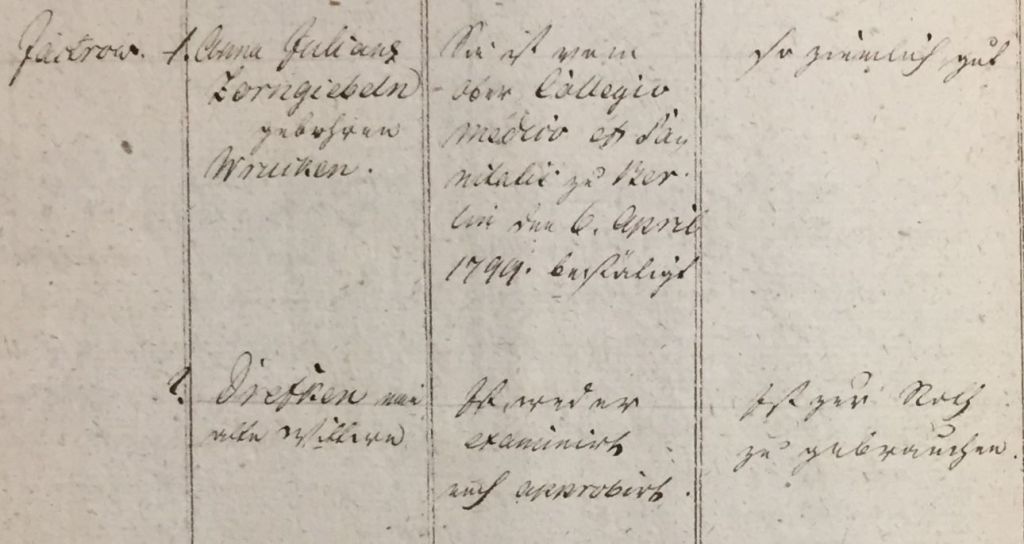

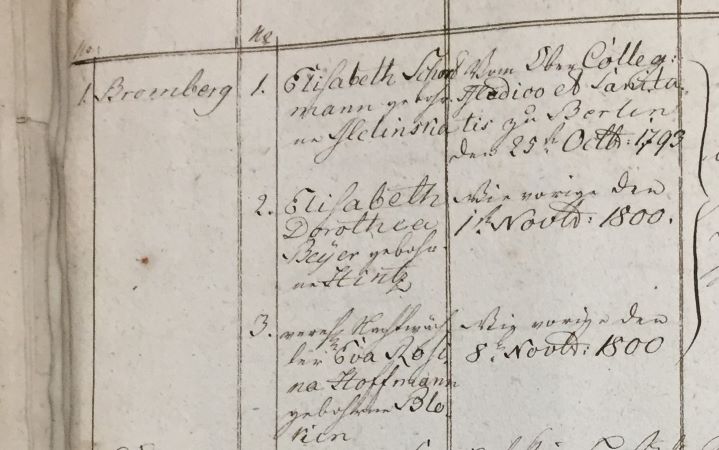

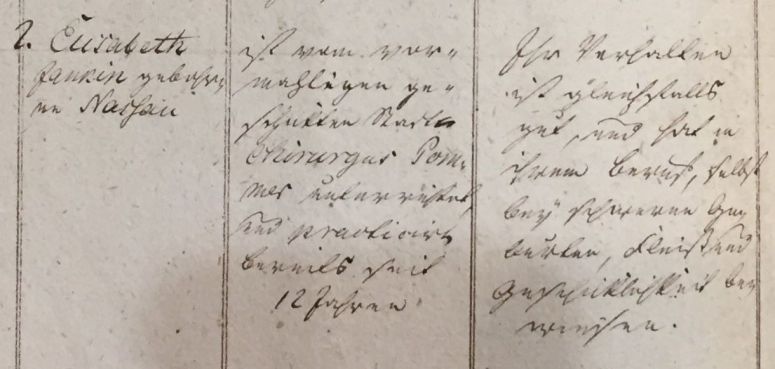

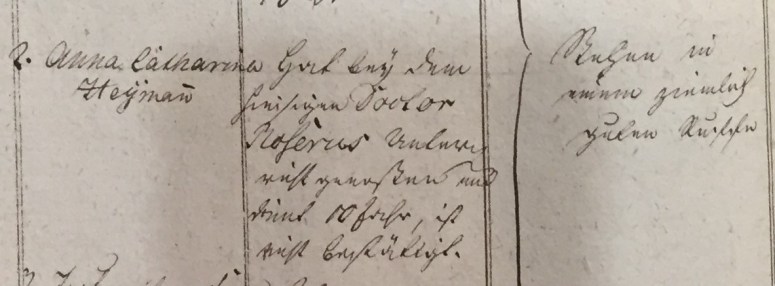

The census of midwives from Netze District was made between 1804 and 1805. What may be surprising is that quite many women quickly tried to meet the new, higher requirements. The list already includes several who graduated from the Collegium Medicum et Sanitatis in Berlin.

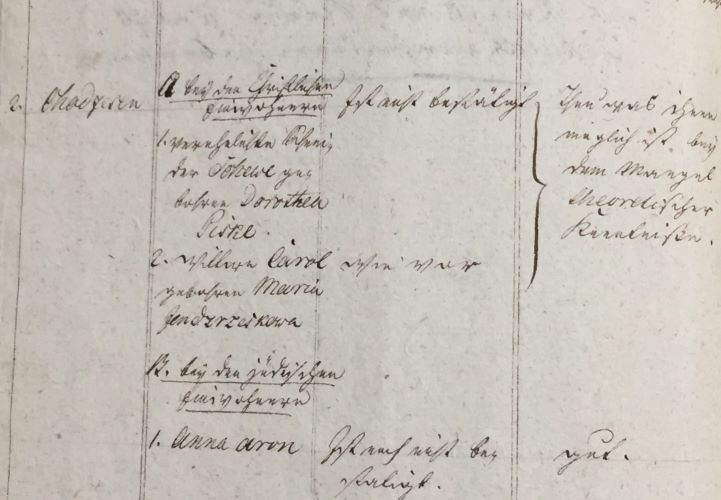

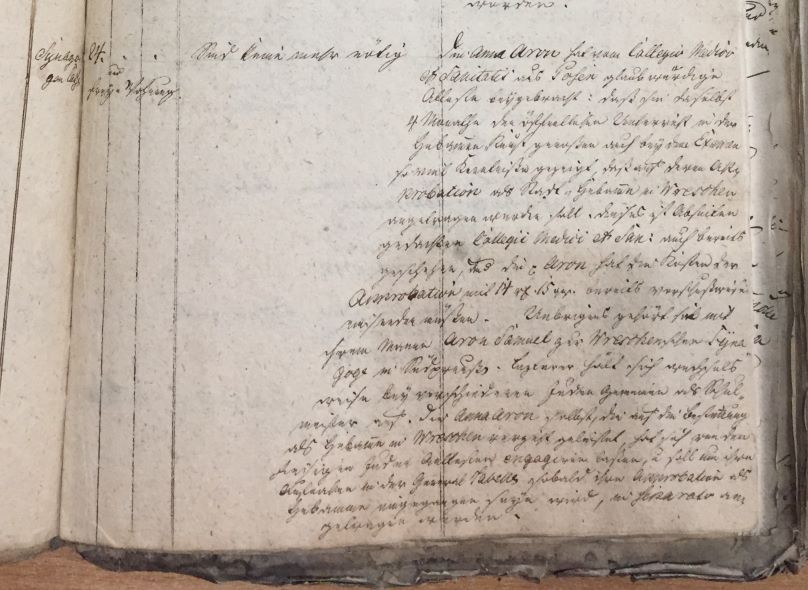

In turn, one of the candidates considered below studied at a newly established school in Poznań.Compared to the third one, the first two candidates’ comments were short and concise. The official said that women giving birth have been using their services for years because they have no other options. In turn, the longest opinion about Anna Aron that I found includes information about her studies. She studied at Collegio Medico et Sanitatis in Poznań. This opinion provides insights into her educational background. It also includes the offer she has already received to work as a municipal midwife in Wreschen. Additionally, her husband, Samuel Aron, is a teacher. This provides us a lot of information about Anna’s marital and social status.

Several other women presented confirmation of their skills issued by a local doctor. These were usually experienced midwives, often widows.

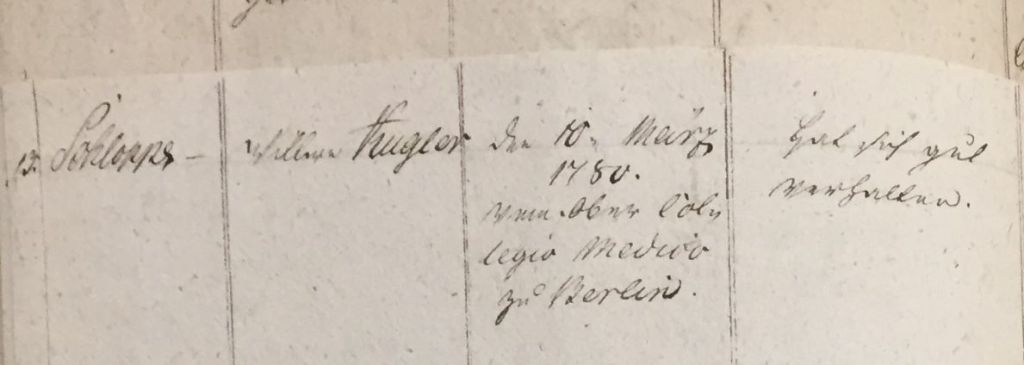

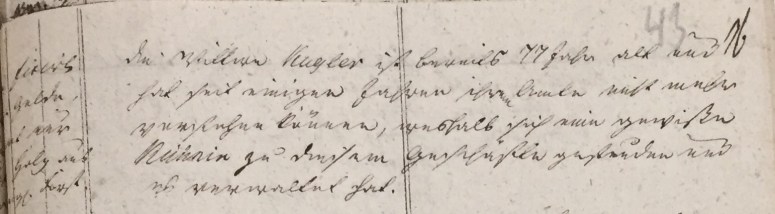

Some, like the widow Kugler, were considered too old to continue with this profession. This was despite their knowledge acquired at Collegio Medico et Sanitatis in Berlin. Their experience and good reputation were also noted. So you can see that many factors were taken into account.

The census includes information on education. It also provides data on age and health. This is specifically important for women. According to officials, women should be replaced by younger ones.

There are also comments about their pay. Some midwives count on payment from the state or the city where she worked. There were not many professions available to women. The combination of increased requirements and extra pay resulted in willing candidates taking the time and costs of education.

Part of the list only provides information about the name of the midwife performing deliveries in a given place. As a last resort, you can at least get information about spelling surname and marital status.

Conclusion

Midwives and women from noble families have formed a distinct group. This group has existed since the end of the 18th century in Poland. They can be found in separate documents devoted to them. It is worth paying attention to this type of documents. They are different from record books. These documents give a picture of the society at that time.

If you are interested in assisting with such a search, contact me on email. You can also contact me if you would like to review specific records that do not have online scans.

https://asklidia.page/services-2/

- I used some historical information from the book: M. Stawiak-Ososińska “Sztuka położnicza dla kobiet. Kształcenie akuszerek na ziemiach polskich w dobie niewoli narodowej (1773-1914)” Warszawa 2019.